Background

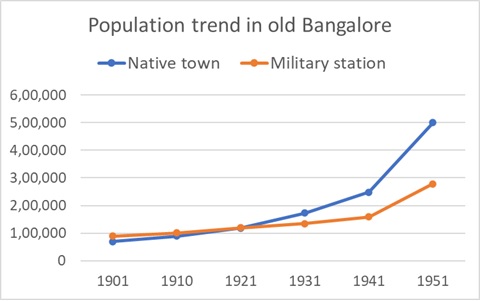

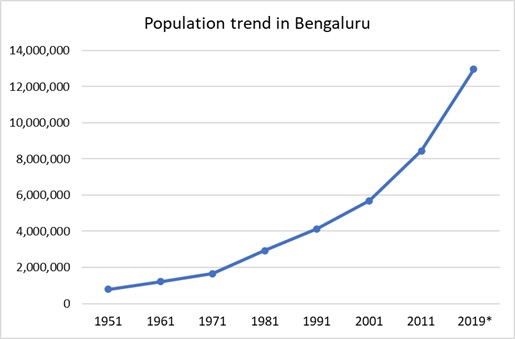

The history of urbanisation in Bengaluru that changed the face of the city can be viewed through three major waves. The first wave was the establishment of a cantonment area in the year 1807 to house the Mysore Division of Madras Army of the East India Company. The growth of cantonment with the expansion of European regiments in the 1840s further led to more migration to this region and people building their lives around it.

This growth in the northern direction of present-day Bangalore was soon followed by the establishment of the City Market, known today as Krishnaraja Market, in 1921. This became a functional and accessible area for all people in the then Bangalore.

Source: Report of the Bengaluru Development Committee: 14 (1954)

The second wave that came about in the history of Bangalore’s expansion is associated with the establishment of many Public Sector Undertakings in the city. They include Indian Space Research Organisation, Bharat Electrical Limited, and Hindustan Machine Tools, etc. This was followed quickly by the emergence of textile and other industries that further pushed the expansion.

The third and major expansion of Bangalore happened by the 1980s around the Information Technology wave. More and more people migrated to the city that transformed itself from a garden city that was pensioners’ paradise to a buzzing hub of neo-liberal economy thriving on IT and BT, along with educational institutions, long-established markets, public sector units and private industries. This dynamic city attracted investment from other countries and became the fourth largest technology cluster in the world.

Bangalore became Bengaluru in 2014. Today, 12 million people call Bengaluru their hometown. Along with the city population, the land area of the city also increased from 69 sq km in 1949 to 2190 sq km in 2019.

Source: Various Census of India reports.

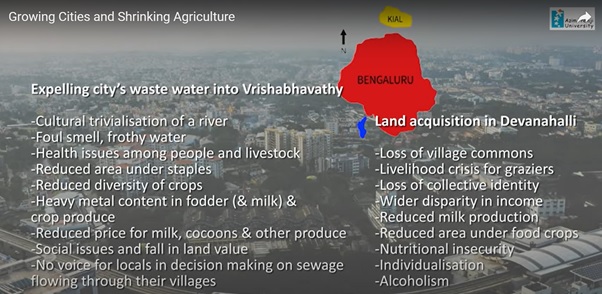

The video ‘Growing cities and shrinking agriculture’ showcases two case studies around Bangalore – how such a city usurps land and how it fouls the water, both of these impacting agriculture and society in direct and indirect ways. Both these are typical impacts/ aftermaths of any growing city. Let’s look at the cases one-by-one.

Land conversion for the new airport –

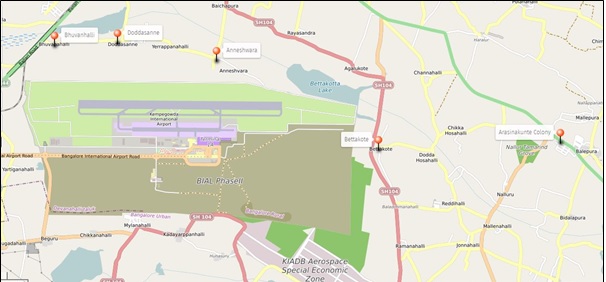

Bengaluru International Airport, established in the year 2008 provides a good example for displacing people and land from agriculture and allied activities, for the sake of urbanisation. It was renamed as Kempegowda International Airport in 2013. The airport is spread across an area of 4009 acres of land in Devanahalli Taluk (KIADB). Land acquisition for the airport was carried out by KIADB between the years 1991 to 2001 when 11 villages lost their land either wholly or partially to this project. Two villages of these 11, namely; Arisinakunte and Gangamuthanahalli were completely displaced. From nine other villages (Bhoovanahalli, Doddasonne, Anneswara, Bettakote, Hunchur, Mylanahalli, Begur, Yerthiganahalli and Chikkanahalli), partial farmland acquisition happened.

Our calculations based on the land records data provided by the village accountants of these villages show that 36 percent of the acquired land was village commons and 50 percent were private lands. The rest 14% was from forests and other kinds of land. Loss of private land ranged from one to ten acres per family in the study villages. A compensation of Rs 5 lakh per acre was fixed for the land acquired.

| Village | Commons | Forest | Private land | Other | Total |

| Bhoovanahalli | 23.08 | – | 60.19 | – | 83.27 |

| Doddasonne | 279.36 | 20.3 | 56.64 | – | 356.3 |

| Anneshwara | 511.19 | – | 171.13 | – | 682.32 |

| Gangamutanahalli | 222 | 3.17 | 353.34 | 3.39 | 581.9 |

| Bettakote | – | 354.19 | 154.26 | 29.14 | 537.59 |

| Hunchur | 226.27 | – | 58.6 | – | 284.87 |

| Arasinakunte | 41.8 | – | 740.6 | – | 782.4 |

| Mylanahalli | 39.2 | – | 148.02 | 3.18 | 190.4 |

| Begur | – | – | 88.32 | – | 88.32 |

| Yerthiganahalli | 19.24 | – | 73.57 | – | 92.81 |

| Chikkanahalli | 12 | – | 87.15 | – | 99.15 |

| Total area of land acquired | 1374.14 | 377.66 | 1991.82 | 35.71 | 3779.33 |

Note: calculated area of 3779 is 230 acres less than the KIADB data of 4009 acres.

Land acquisition included that for the airport operations, industrial property development and special economic zones as a means of financing the airport project between 1997-2001. Coming of the Airport brought with it an ongoing increase in demand for land in the surroundings for upper-class residential layouts and industries. During our field visits, we heard of many new land conversions for setting up industries.

Let us focus on the livelihood and agricultural patterns in the acquired villages and other surroundings of the Airport. People from the completely acquired villages were relocated in another village as a new single hamlet. They were given small housing sites without farmlands. Most farmers from the villages that lost partial agricultural land continue to farm the patches remaining with them. They shifted to cultivating roses from the diverse set of crops that they used to grow – vegetables, paddy, mulberry and ragi. Rose flowers fetch them good income but cause health complications from the usage of excessive chemicals in its cultivation. A few farmers are still engaged in sericulture, growing mulberry in the little piece of the remaining land. A few villages still have shepherds grazing their sheep through the day.

Jobs available for most people are in short-term informal non-farm occupations. Around 130 youngsters from the 11 acquired villages work in the Airport, shops inside the airport campus and some nearby industries. At the Airport, they are generally in gardening, driving, security keeping, housekeeping, loading and unloading.

The compensation money for the acquired land was used by many to build single building apartments for renting out to migrant labour coming to work in the new industries around. Rental income from these tenements has become a new source of livelihood for the well-to-do in the partially acquired villages.

Let us now focus on the two villages that were fully displaced; Arisinakunte and Gangamuthanahalli. Around 140 households were displaced from these two villages. They were given compensation not just for their farmland, but also for the houses lost and also for other assets like wells, trees and livestock owned. People from the two villages were moved to the village commons of a village named Balepura, far from their original village as also from the airport. They received housing sites as mentioned before, depending on the size of their families. This hamlet was named after one of the two acquired villages, as Arisinakunte colony.

For most resettled families, the compensation money was just enough for building a house and/or spending on marriages, health care, buying automobiles, pilgrimage and loan repayment. Hence most of the 140 displaced families have not been in farming since 2001 – 2002. Older people still try to cultivate in the little patches around the colony. Women seem to have no external engagement except a few younger women who work at the airport. Older women search for work as farm labour while others try running small business enterprises like a grocery store, milk agency, etc. A few of them bought one or two cows for supplying milk to the dairy society in the colony. With grazing areas acquired for the airport, milk production has declined drastically in the area. Many say they would like to get back to farming if they had access to a piece of land somewhere in the surroundings.

Even after two decades of land acquisition, displaced people are yet to adapt to the changing landscape, livelihoods and social mix. Farming lost its primacy as the sole or main source of income either as farmers or as wage labour. Still, agriculture seems to be a preferred option among middle-aged villagers (especially women) as a secure and dignified livelihood. They say money comes and goes from their hands, more than the pre-airport times. Individualisation, alcoholism and health issues are more persistent outcomes in their lives.

Wastewater in the river stream

Having seen changes brought out by the expansion of urban infrastructure for and around the airport, let us now turn to the aftermath of Bengaluru’s expansion on the quality of water in its surroundings. We examine this impact of the city through its impact on its’ sole river – Vrishabhavathi.

Originating in the Bull Temple in Basavanagudi in the south-western part and the Kaadumalleswara temple in Malleswaram to the North of the city, Vrishabhavathi flows through localities like Jnana Bharathi, Rajarajeshwari Nagar and reaches Bangalore’s outskirts at Kengeri. Winding around Kengeri and Bidadi, the river enters Byramangala reservoir to join Suvarnamukhi river later, at Kurubarahalli. Both together flow as river Vrishabhavathi and then joins Arkavathy at Ganalu, and flows till Mekedatu to join Cauvery. Before Vrishabhavathi enters the Byramangala Dam, it is intercepted at two STPs.

This river with several temples on its bank had major religious importance till about two decades ago. People used the river water to bathe, cook and drink as well. Villages on its bank used this water for cultivating vegetables, paddy, sugarcane, flowers, mulberry and ragi. Bengaluru expanded and so did the waste it accumulated and dumped. This water body is being treated as a sink to dispose of wastewater from the city’s dwellings, shops, offices, educational institutions, hotels, industries and other establishments. The industries dispose of their effluents into Vrishabhavathi with minimal or no treatment. Its’ water with toxic effluents is no longer fit for human consumption. Effluents from industrial estates deteriorate the living environment and farming conditions in the downstream areas.

Let us take a look around 12 villages among the many that use Vrishabhavathi water for agricultural needs today. The stretch we are going to cover is from Byramangala reservoir to Kurubarahalli to the south of the reservoir.

The first impact of sewage water from the city is the change in crops cultivated. Farmers are now forced to limit their crops to what can be grown with the water: fodder, mulberry, coconut and baby corn. Food crops like paddy, ragi and vegetables have been reduced drastically. For meeting their requirement of staples and vegetables, they are dependent on the Public Distribution System and markets. With the increasing area under fodder as that grows well in the polluted water, dairy farming has taken over as the major source of farm livelihood. Each house around the irrigation channels from Byramangala has an average of 3 to 4 cows. Dairy cattle take away many hours of their everyday life, forcing the whole family to engage in it in some way or the other. Many women stay home just for dairy farming. Milk and mulberry silk are being touted as the two livelihood pillars in this region. Off late, they both suffer from declining quality and price. Baby corn is another crop that is grown by many in this region, on contractual arrangements with retailers and aggregators from the city. Thanks to the absence of food safety tests in the city’s vegetable and fruit shops and food joints, baby corn and other crops grown in polluted water find a regular market.

Though a majority of villagers in this region are engaged in agriculture, youngsters are moving towards the industries in Bidadi and Harohalli region. Thus, while polluting the water bodies, industries also pull agricultural labourers from their surroundings.

The sewage water has not only impacted farming in this region but also has given rise to health issues like skin rashes, allergies and diseases spread by mosquitoes. Socio-cultural impacts are also common. Villagers hesitate to offer drinking water to visitors, they no more do the customary river worship and young men complain about the difficulty in getting brides to come and live here.

Despite some conflicts and protests about this issue, efforts from the concerned government departments have not been effective so far. A new dimension has been added to the pollution issue in terms of a diversion of Vrishabhavathy water after effective treatment. There has been a diversion of water from the Byramangala dam and further talks of water treatment, but farmers were not informed about the same. Lack of convergence among various government departments has left the farmers in this region perplexed. If they will have to trade off their available access to (polluted) water, is haunting the farmers of Byramangala.

Concluding remarks

These two impacts of Bangalore acquiring rural land for its airport and dumping city sewage in Vrishabhavathi are typical examples of what an expanding city can do to farming in the peripheries. The impact doesn’t confine to the land, water and people in the peripheries, but also on the people living in the cities, since they end up consuming the produce from the city peripheries – like milk, coconuts, baby corn all with residues of toxic heavy metals.

Lack of dialogue between consumers in the city and producers of their food is hampering possible harmonious integration of the city’s expansion with rural livelihoods.

Urbanisation process should involve collective informing and deliberating processes for urban and rural societies on their mutual impacts. If consumers and producers feel responsible for the impact of extracting land and dumping waste as also of producing unsafe food respectively, the process of urbanisation could be smoother and more rewarding to the larger society.

For more information about the two case studies discussed in this blog please visit –

Urban wastewater for Agriculture: Farmers’ perspectives from peri-urban Bengaluru (APU Working Paper 20)

One-part farmers – villages two decades after land acquisition for Bengaluru Airport (forthcoming)

(The video is an output from the project titled “Ecosystem Services, Agricultural Diversification and Small Farmers’ Livelihoods in the Rural-Urban Interface of Bengaluru” implemented at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru under the Indo-German Collaborative Research project (FOR2432). Financial support from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India is duly acknowledged.)