Seema Purushothaman

Small holder farmers are quite a common presence in India. To a general reader in urban areas, any mention of small farmers summons imageries of a tiny piece of land where a family struggles to eke out a living. Popular perception is that they are not financially viable and hence these families should either scale up or liquidate their farmland and/ or join other sectors[1]. But literature also urges us to not be so hasty; it establishes that there are many social purposes that these small farm families in India fulfil that are important to recognise[2].

Data on land holding patterns attribute a specific extent of land area to the small farm holdings. This land size bracketing of ‘Small & Marginal Holdings (SMH)’ often camouflages the diversity that exists within this group. An obvious divergence within this class of farmers arises out of their varying size attributable to agro-ecological variations. Small holdings in very different agroecologies like hilly terrains and plain lands obviously differ in their average size. But they also differ in the kind of farming undertaken. Field crops of staple food grains are common in the flood plains and the vast dry hinterlands, while diverse crops ranging from short duration herbaceous plants to large perennials dot the hilly terrains. Both these landscapes also host distinct animal & bird components too. Small farmsteads in the hilly regions are known to host high agro biodiversity.

However, certain other differences within small holders are not as obvious as the size of holding, or crop-animal combinations aligned to their terrain or bio-geography. These factors constitute the criteria that distinguish family farms from other small holders. How distinct is this entity – ‘Family Farm’ (FF) from the usual typology of SMH? The characteristic features of Family Farms are unpacked in the next paragraph, before dwelling on the future of this entity.

What characterises a Family Farm (FF)?

Even though the presence of purely market/profit oriented small farmers is quite visible, for many family farms in the rural landscapes, agriculture is equally important as a way of life. For many of them, often (-not always) the livelihood element is subsidiary. Family farming continues to be crucial as a familiar occupation, culture, skill, and identity. The second distinguishing feature of family farms is the high proportion of family labour in production activities, though hiring and sharing of labour available within the locality are also prevalent. Their third distinguishing feature is the relatively high share of household consumption from what they produce, though these farm families will continue to be net consumers of agricultural produces, given the small size of operational land with them, relative to family size.

The fourth characteristic is that even when a family farmer owns the agricultural land (-mostly inherited), she may also be leasing land or will be engaged in wage labour; the latter spread across off farm and/or non-farm engagements. The fifth and the more significant fact about family farmers as a class, is that they are invisible in the popular and political discourse, while being omnipresent.

With the above five features, it shouldn’t be difficult for the reader to distinguish FFs from other SMHs. In contrast to the FF, a non-FF SMH could be a) capital intensive enterprise operating exclusively for profit making, b) too marginal holding of a family engaged in other occupations or c) urban hobby farmers conscious about healthy food.

Family farms – a glimpse into their Past and Present

This essay distills pertinent conclusions drawn from studying 168 farmers and 32 farmer migrants from 16 villages across five districts that were identified systematically following selected criteria from the book – City and the Peasant – Urbanisation and Agrarian Change in South India (Purushothaman and Patil (2019)).

Historically SMH used to be producing exclusively for subsistence and for paying tax to the government concerned. Their plight across the tenurial and governance history of respective regions is an interesting study and analysis. For such an exploration into the history of small agriculturists in the old Mysore and Gulbarga regions please see Purushothaman and Patil (2019). A birds’ eye view into the history of small family holdings identified in the previous section reveals that they belonged largely to marginalised social groups. They lived on small parcels of land with insecure tenure and without much ex-situ engagements for livelihood. But a notable proportion of such FFs in history also were engaged in other livelihood options present in the rural landscapes itself, like weaving, pottery, metal/ clay works etc. Towards the second half of the 20th century, the process of settlement of tenurial rights in favour of actual cultivators was started in parts of India. It is well accepted now that such progressive land reform measures were too weak to override rural power hierarchies in most agrarian landscapes. Thus, unfinished land reforms left the agenda of equitable distribution of agricultural land largely unaddressed. The size and quality of land holdings that ultimately got distributed were inadequate to meet the essential needs of a farm family.

Even then, the persistence of FF in India is notable (though their exact numbers are hidden under the larger category of SMH coming to more than 125 million in Agriculture census 2015-16). That poses the question – why and how do they persist through centuries into this era of neo-liberal economies? Is it a resilient persistence against all odds, or is it just a desperate survival? Answers to these questions have been explored in detail for the state of Karnataka in Purushothaman and Patil 2019. They reinforce the argument mooted in the first para of this essay, on why we shouldn’t underestimate the crucial role of FFs.

FFs in early literature referred to as ‘peasantry’, and later on mostly as SMH farmers have been mostly perceived as an unviable primitive mode of production. Some recent literature laud them as a model for sovereign food systems ensuring ecological and nutritional autonomy, or as a cultural value based circular economy[3]. Others locate them at the other end of the corporate food regime as the ‘need’ economy of reserve army consisting of footloose labour, for producing cities for the ‘greed’ economy. The book reveals the gaps left collectively by these depictions of SMH in dis-ambiguating FFs of today. These gaps mainly pertain to the plural identity of FF and their embeddedness in the larger social-ecological commons – interconnected systems of forests, water bodies, soils and pastures.

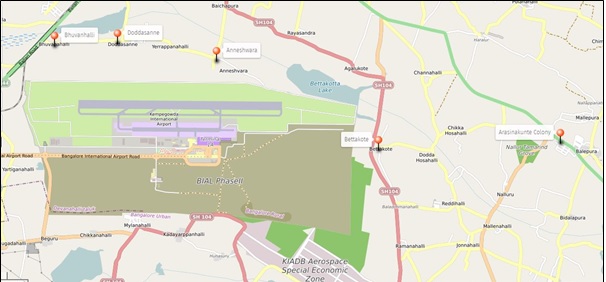

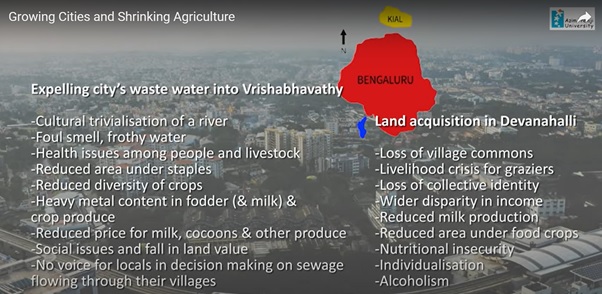

The study sites were located in four different assemblages of urban and agrarian landscapes. Site specific chapters in the book tease out the out flow of land, labour, water, and farm produces from small farms to the urban areas as well as the flow of investments and effluents from urban areas to the production landscapes around the the city. The quantum and impacts of these flows vary between the four assemblages and determined the plight of small family farmers.

The concurrent impact of the above mentioned flows determined the plight of FFs, as rural agrarian life was getting choked by inadequate and low-quality public delivery systems of health care and education. Meanwhile, failing bore wells, drying irrigation canals, declining soil productivity, and mounting loans that came with the spread of irrigation and intensive monocropping to feed the urban demand, drove vulnerability among FFs in most study villages, in the medium to long term. This vulnerability of rural agrarian family farms desperately seeking short term advantages, was manifested in a) indebtedness (loans taken for a variety of reasons like health care or for customs related to death and weddings) and b) out-migration from rural areas as also from farming, with women & lower social strata getting pulled towards urban life, despite low-quality housing in the cities.

The question that these FFs were trying to grapple with was mostly about when, and for how long to migrate. A pattern of vulnerability emerged from the ways in which FF tried to navigate this uncertainty. This pattern is briefly mapped in the section below.

A typology of Family Farms and their probable Future:

As mentioned earlier, despite the challenges outlined, FFs are easy to spot, if you look for them. The FFs described in the book could be classified into the following types, based on the extent and nature of vulnerability in their continued existence. Persistence of FF in the study sites ranged from resilient long-term existence to types of economically vibrant but unsustainable existence, or existence as low yielding but environmentally sustainable systems.

FF persisting with resilience were found in mostly rainfed villages that had farming systems corresponding to their agroecology and local demand pattern. Typically, these families farmed staples (e.g., finger millets) intercropped with perennial cash crops (e.g., mango or coconut) along with suitable livestock (sheep, goat or dairy cattle). Here the quality of soil and water resources was intact and nutritional security of the families was ensured. These FFs found spare time and money to attain educational qualifications, that enabled them to take advantage of emerging non- farm, non-rural opportunities. This system that leveraged the nourishment and livelihood objectives of agriculture with non-farm engagements of various kinds, emerged as the lone model of FF in the study sites that seemed to have a future of its own.

FF trapped in poverty: Not all rainfed farms offered the above promise for future. Rainfed interior villages with monocropping of cash crops that too on unequally distributed land with exhausted soil, water, and biomass were trapped in poverty. These FF also reported high morbidity, medical expenses, and indebtedness. Outmigration was the only coping mechanism, if not an escape route for good.

FF with high capital turnover, commonly found in peri-urban Bangalore are profitable businesses. Profits are realised despite exhausted soil and water, heavy dependence on synthetic inputs and high interest credit. These small holders were found to be awaiting the arrival of real estate fortunes, ready for occupational migration to new informal engagements offered by the city.

FF locked in dependent, inefficient and unsustainable practices showcase a deceptive transient prosperity. Canal irrigated monocultures heavily relying on input subsidies, credit and public procurement of outputs, maneuvering the declining productivity and shrinking choice in farming options are examples for this type of FF without a future of their own, unless retained on the public funded financial ventilators pumping producer and consumer subsidies.

Gleaning the above typology, how to foresee the future of FF? The following are elicited as potential factors to enable continued harnessing of the social benefits of ecological and nutritional security offered by FFs. They are 1) secure access to minimum required land for a family farm to meet their basic needs 2) proximate and consistent buyers (consumers and processing units) for their small surpluses 3) ensuring quality of soil, water & biodiversity 4) effective public facilities for higher education and health care, and 5) rural nonfarm employment that does not undermine any of the above enabling factors.

Acknowledgement

Inputs on the earlier draft of this write-up from Gayatri Menon are greatly appreciated. Usual disclaimers apply.

[1] See George V.K. 2018 or Fan and Chan-Kang 2005, for popular arguments on why small holders should either move out of farming or scale up. Discussion in Nair et al. 2020 on contract farming indicates how most farm policies do not benefit small holders.

[2] See Purushothaman (2019). The Science and Economics of Family Farms. Current Science.

[3] See the discussion in Ploeg 2013. Food Sovereignty – a Critical Dialogue.

‘Blue sheds’ as they are referred to are the shanties where migrant workers stay in Bengaluru.

‘Blue sheds’ as they are referred to are the shanties where migrant workers stay in Bengaluru.  An interior hamlet from where smallholders migrate to insecure jobs and abysmal living conditions in some distant city

An interior hamlet from where smallholders migrate to insecure jobs and abysmal living conditions in some distant city